Executive Summary

Most organisations are good at managing scope creep. We reduce projects to an MVP. We define the budget. We understand the trade-offs.

We then ask for time estimates — often broad ranges, grounded in uncertainty and constrained by the scope and cost already chosen.

The subtle shift happens after approval.

We aggregate those estimates, add a little buffer, and communicate a delivery date based on the estimates. That date quickly becomes a commitment.

In doing so, we attempt to constrain time after we have already constrained scope and cost. We are trying to pull a lever we no longer have access to.

Nothing about the underlying assumptions has changed — but now the expectations have.

When forecasts are treated as promises:

- Risk is masked by optimism.

- Pressure replaces planning.

- Scope is quietly eroded to protect the date.

This is not an argument against discipline or accountability. It is an argument for clarity.

If a date is truly non-negotiable, that is a conscious funding and risk decision — not a scheduling artefact derived from estimates.

If scope and budget are the chosen constraints, then time must remain a forecast.

You can only pull two levers.

Be explicit about which ones you’ve chosen.

Estimates are forecasts. Dates are commitments.

This might not sound like your typical IT governance post, but I promise it will all make sense at the end (maybe).

A little while back, I had a conversation with a good friend who was frustrated with their plumber after a recent ‘failed’ project.

“How are you? I asked politely.

“Oh, I’m so mad; have I told you about the issue we had with our plumber?”

Oh dear. This sounds serious.

“No. What’s going on?”

The Project

In this instance, the ‘project’ was that their family (parents, uncles etc..) was travelling from overseas to stay with them on relatively short notice - a few months.

Luckily, with only two people living in the house, they had the space (rooms, kitchen) in their house for their family to join them. However they had not really used the ‘spare’ bathroom - which they would now need. As it turned out there was an issue with the shower which would need a tiler and a plumber to resolve. They immediately arranged for a company to come and fix it.

A few weeks later the plumber arrived bearing bad news. The pipes behind the shower had all corroded and had been silently leaking behind the wall. The entire wet wall would need to be pulled down, dried out, fixed and re-tiled. It was a big job. The tiles themselves were also unique (part of the charm) and they didn’t have anything close to matching available. They would need to be ordered from overseas.

I only have the word of my friend here, but he claims it was “promised” to be done in time for the family. At the very least it was strongly implied it would be done by the time the family came to visit.

As you have probably guessed by now, the bathroom was very much, not complete by the time the family visited.

Here are the cliff notes:

- Due to the ’tariff turmoil’ tiles / shipping became way more expensive and discontinued.

- Changing the tiles would mean a less matching bathroom.

- The wet wall that was originally used didn’t conform to the current building codes and the new code required thicker walls requiring additional work.

- Plumber was unwell for a week.

- Tiler was unavailable for a time by the time the plumber had finished.

- The whole project ended up at twice the cost as the original quote.

- Family had one bathroom with 6 people in the house.

In this instance, most people’s default position is to immediately jump into the blame game.

- The contractor should have …

- Your friend should have ….

Some or all of that may be true. However operating in hindsight is always much easier.

I’ve subsequently visited my friend’s home and seen the bathroom first hand. It is beautiful! The plumbers / tilers have done a wonderful job. From a visitor’s or prospective buyer’s perspective, the project would have been a success.

If you look at how each party acted at each stage throughout the project, it’s all fairly reasonable behaviour. No one is acting with bad intent, everyone is trying to get to the same outcome and in the end my friend got an excellent bathroom at what was a very reasonable price.

Yet, my friend was not happy and my read of the situation, is that the contractors were pretty eager to be done with the whole thing too.

From his perspective, this project failed.

Does this sound familiar?

Almost every significantly sized engineering project experiences these same challenges. I’ve personally been on both sides of these efforts and I’m sorry to say that 27 years into my career I haven’t yet found the silver bullet. I’m fairly sure if you’re reading this you’ve been in a similar position.

That doesn’t mean that we’re all doomed and I strongly believe that most projects success / failure is largely an artefact of perception. I’ve personally experienced two projects that were simultaneously viewed both a miracle and a failure. I could very much see both sides.

I would argue this is more often the case than people are willing to admit.

What’s in a date ?

Before going too far I want to very clearly distinguish an Estimate from a Date.

Estimates

I came across a few articles like this one How I estimate work as a staff software engineer from Sean Goedecke and this one Estimates – a necessary evil? from Erik Thorsell. I like these because they both give great insight into the challenges of estimating technical work and how these estimates are subsequently used by the wider organisation.

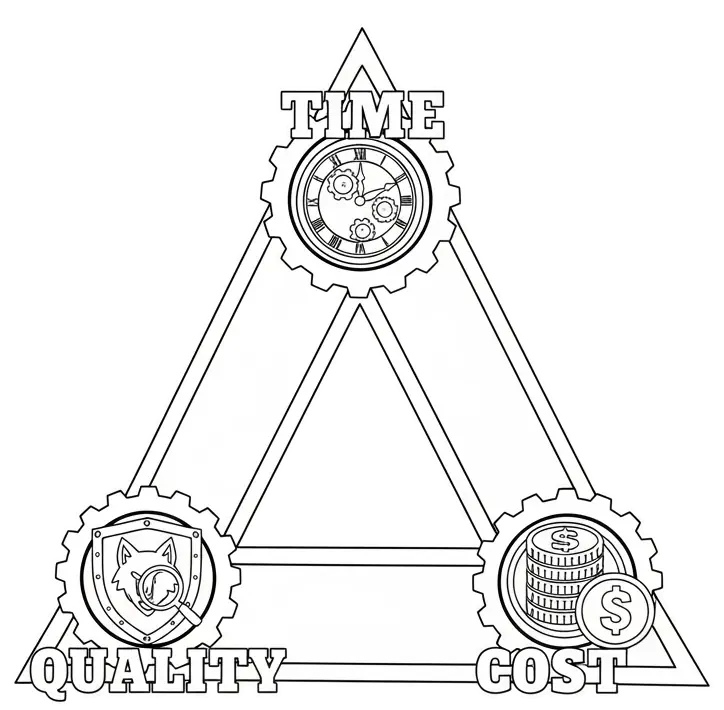

Most people inherently understand that when we ask someone for a time estimate they are providing a range, based on the available knowledge at the current point in time. Additionally these are almost always provided in the context of an existing trade-off in the [“Iron Triangle”] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_management_triangle).

As an example, if you’re aiming to deliver an MVP with a budget of $2m then you’ve actually already chosen the two levers you get to pull. You can’t sacrifice scope as it’s already the Minimal Viable Product and your budget cost is fixed. Even if you have some flexibility in the budget, it’s still bounded. The trade-off must be time.

If we look at our bathroom project, there are legal requirements that the contractors have to meet in terms of quality standards. I’m sure if my friend was willing to pay $2m the tiler would have been happy to get on a plane to Italy to collect the tiles and ensure they hit the deadline. Was that really an option ? Possibly, but it’s much cheaper to put your family up in a nice hotel.

We absolutely need estimates. They are essential for us to frame our thinking and make good sound decisions.

Dates

“A particular point or period of time at which something happened or existed, or is expected to happen.”

We care about dates because at that point in time, something changes. Customers are on-boarded, sales happen, funding runs out … It is a fixed point in time and it’s a finite resource.

It’s important to acknowledge that once a date is assigned to a project, then effectively you have chosen to pull the time lever. Either costs or quality / scope have to give. In an engineering project, consider that if your initial estimates were based on an MVP, then effectively you’re cannibalising the underlying framework of the project to the degree that you end up spending more time through unintended side effects.

Estimates vs Dates

The mistake that often occurs is that ‘we’ (people, the industry, you, me) naturally want to use those estimates to derive a date.

On the surface this seems like it makes sense; If Sally takes 3 weeks to make a widget then Jenny and John have said it will take 1 week to incorporate it, 2 days to test it, add a bit of buffer 5 weeks…we’re golden right ?

Baked into those estimates are often layers of assumptions which individually to the actors represent a small risk, but can easily compound.

Sally has made the widget but it uses a newer version of the JavaScript library than is currently used in the site. As seasoned developers Jenny and John were worried about this. Luckily they baked in enough time in their estimates for this work and still manage to hit their targets. Unfortunately, during testing, it has surfaced some regressions. Nothing major, but Jenny is now on the critical path for another project, John is looking after his Dad who is currently in hospital and an agency will take some time to get onboarded and learn the codebase. In turn that agency probably has somewhere in their MSA that they require an existing company representative to be available for questions / guidance.

Don’t derive dates from estimates

Both Sean and Erik go into more detail on the effect of using those estimates to establish dates. The TL;DR is that teams (including 3rd parties) buffer the estimates to the extremes, which then invariably blows out the cost. This ultimately culminates in a situation where engineers are given an “acceptable estimate” or features being removed so as to match the budget. This is sadly the situation that most organisations find themselves in today.

The impact of dates.

In both cases it’s pre-emptively addressing issues that haven’t yet occurred. More importantly, in any reasonably sized project, once you start removing scope, you really need to re-gather estimates from everyone.

Removing a widget from a screen may not have much of an impact to the rest of the project but it’s also unlikely to substantially reduce the delivery time. Changing an Identity Provider on the other hand…

The second you derive a date from the estimates, you are adding a constraint which wasn’t present when creating the estimate.

“You Can Only Pick Two: Fast, Cheap, or Good”

The problem isn’t dates. The problem is treating estimates like commitments. When you derive a date from estimates, you are masking risk with optimism.

What needs to change ?

Within our Iron Triangle, we tend to treat the “quality / scope” as something flexible. I have yet to come across a project that had been delivered that was excessively high quality. No one is delivering substantially more than is required.

As an industry, we’re aware of scope creep and have the necessary tools to manage it. While it’s technically possible to reduce the scope of the project, in mature organisations it’s rarely possible to reduce quality /scope without incurring additional downstream cost and risk. There is only so much you can remove before it’s no longer fit for purpose or worth while. The lever is more or less fixed at this point.

So how does this view help from a governance perspective:

- For projects where a specific date is life or death - own it from the start and be ready with the CFO. This is an intentional choice to trade cash for a specific deadline. Consider impactful, project wide bonuses or incentives early. You need everyone singing the same sheet from the get go.

- If you have an absolutely fixed date and a fixed budget (e.g federal government funding) - be clear with your team and your vendors. You are asking “What can I get for this in this time”. It may not be worthwhile.

- If you have a fixed (or mostly fixed) budget, don’t confuse forecast with commitment. Be clear why. You have pulled the two levers already. To quote Disney’s most famous Queen “Let it go”.

Managing risk

Just because you’re accepting reality, doesn’t mean governance goes out the window. I’m not suggesting for a second that we don’t monitor progress towards the goal and if anything you should find clarity as you’re focusing on what you can actually (and have explicitly chosen to) control.

Tracking real-world time against the estimates and monitoring expenditure is essential. If these are higher than anticipated it’s a good sign that something is more complex than initially estimated.

When you are transparent about what you are committing to: Are we hitting a Date or Budget - then it allows you to focus on mitigating the real risk and plan for those scenarios.

- What is our plan if delivery is close to Christmas?

- What are our operating costs running two systems in parallel?

- Is this approach even viable?

- As a company we want this, but do we have enough capital to pull it off?

The perception shifts from fire-fighting to following the plan.

Be vocal

As a consultancy, we participate in projects, but we don’t control them.

If you believe this is the right approach, set that expectation from the outset.

When teams trust that uncertainty won’t be punished, estimates will become more accurate. More accurate information allows better decision making. It can take time to build back that trust, but you might be surprised at how much more palatable the estimates are.

Governance failure occurs when organisations turn probabilistic forecasts into fixed commitments without changing funding or scope assumptions.

By explicitly stating what you are accountable for and where the tradeoffs have been made, it creates reasonable expectations.

Don’t let a date get between you and a successful project.